Blog

2020.04.24

Best Practices for Working with Configuration in Python Applications

Tobias Pfeiffer

Engineer

Most computer applications can be configured to behave a certain way, be it via command line flags, environment variables, or configuration files. For you as a software developer, dealing with configuration comes with challenges such as parsing untrusted input, validating it, and accessing it on all layers of your program. Using Python as an example, in this blog post I want to share some best practices to help you handle configuration safely and effectively, and I hope to convince you that these are reasonable principles to follow in your own code.

Introduction

All but the most simple programs have a set of parameters to control their behavior. As concrete examples, consider the output format of the ls tool, the port that nginx listens on, or the email address that git uses in your commit messages. Depending on the application size and complexity, there may be many such parameters, and they may affect only a small execution detail or the overall program behavior.

When you deal with configuration, there are various aspects to consider: First, how is it passed into your program from the outside, parsed, and validated? Second, how is it handled inside the program, accessed, and passed around between components? Depending on the type of application, you have to consider how it can be inspected by the user and updated while the program is running. From an operational point of view you may have to think about how multiple configurations are managed, tested, and deployed to production.

Each of these topics can become quite complex and deserves in-depth treatment of its own. However, in this blog post I want to focus only on the second aspect. I will present some guiding principles for program-internal configuration handling that proved useful in the past and that I would like to recommend for anyone developing small to medium size applications.

In the past, I built and maintained applications in various programming languages such as Go, Scala, and Python. In this blog post I want to use Python as an example, because its dynamic nature allows for a lot of things that increase development speed and flexibility (modifying classes at runtime, for example), but may make maintenance and refactoring harder in the long run.

A Simple Example

When talking about the big ideas how software should work and how components should interact, sometimes it is hard to see the connection to concrete code. To avoid this, let’s jump right in and see a code example with a number of issues that I want to address in this post:

start_server(port=os.environ.get("PORT", 80)) # wrong type if PORT is present server_timeout_ms = config["timeout"] * 1000 # let's hope it's not a string database_timeout = config["timeout"] # reuse config key in different context if has_failed() and config["vrebose"]: # typo will show only on failure logger.warning("something has failed")

In the comments I already gave some hints on what may be bad about that code, but let’s explore it in more detail now.

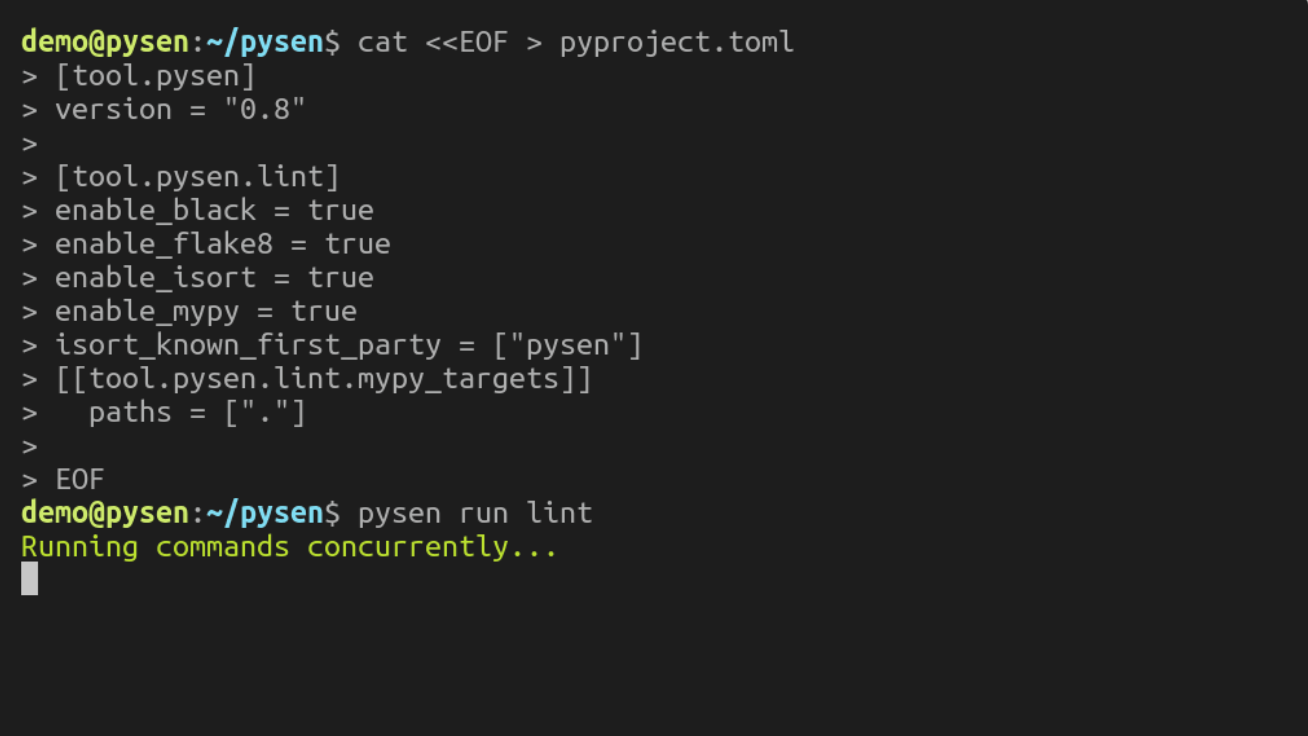

Guiding Principles

Programming is an intellectually challenging task, so I believe that we as software engineers should delegate as many complicated tasks as possible to our tools, such as IDEs, linters, formatters, compilers, or type checkers. If there is a way to find bugs and improve code quality using a tool, then I think this justifies writing the code in a way that such a tool can be used.

Also, if there is a bug in the code in spite of our careful checking and using tools, then it should be reported as soon as possible when the application starts up, should lead to a big warning message and, in many cases, the program exiting right away. Nothing is worse than discovering that some configuration key is missing in the middle of the night, hours after a seemingly successful deployment.

Based on these foundations, I think that a data structure for handling application-internal configuration should follow these four principles:

- It should use identifiers rather than string keys to access configuration values.

- Its values should be statically typed.

- It should be validated early.

- It should be declared close to where it is used.

Let me explain these principles and their consequences below.

1. Use Identifiers over String Keys

Maybe related to a certain “JSONification” of file exchange and serialization formats in recent years, the string-keyed dictionary that can hold anything as a value – Dict[str, Any] in terms of PEP 484 – seems to have become the one-stop data structure for many Python developers. It’s very straightforward to just json.loads() a JSON-formatted string into a Python dictionary and then access it everywhere like config["port"] or config["user"]["email"], as I did in the introductory example. (This approach is not unique to Python, for example the Lightbend configuration library for Scala also has an API like conf.getInt("foo.bar").) If a new configuration entry is needed, just add it to the JSON file and use it right away all over the code.

However, there is a number of drawbacks to this approach:

- It is not possible to detect inconsistent spelling, for example whether a key was

"user"or"users". - If there is an inconsistency, there is no single point where the correct schema is defined. Correct is whatever happens to be in the dictionary.

- Missing data is not discovered until the data is actually accessed.

- Renaming a key cannot be done using IDE/tool support, but all occurrences of the string need to be found and replaced.

- Tools that check consistent formatting of variable names cannot be used.

- Repeated string parsing and dictionary lookups are unnecessarily expensive.

So rather than using string keys – in a dictionary or as a parameter to some get() method – I recommend to use identifiers. The straightforward method is to use class members, and then write config.user.email rather than config["user"]["email"]. Note that Python’s dataclasses (introduced in version 3.7, but available in 3.6 via the dataclasses module) are very handy to hold this kind of data.

Doing so solves the problems listed above:

- In compiled languages the compiler obviously tells you right away if there is a spelling mistake, but also for Python a sufficiently modern IDE usually points out if an undeclared variable or class member is used.

- The class definition is the one ground truth that defines what the correct name is.

- Even in Python it can happen that a declared variable has not been initialized (see PEP 526), but in many cases the IDE or linter tells you about it.

- Renaming is easily done using IDE support.

- Normal formatters or style checkers can be applied.

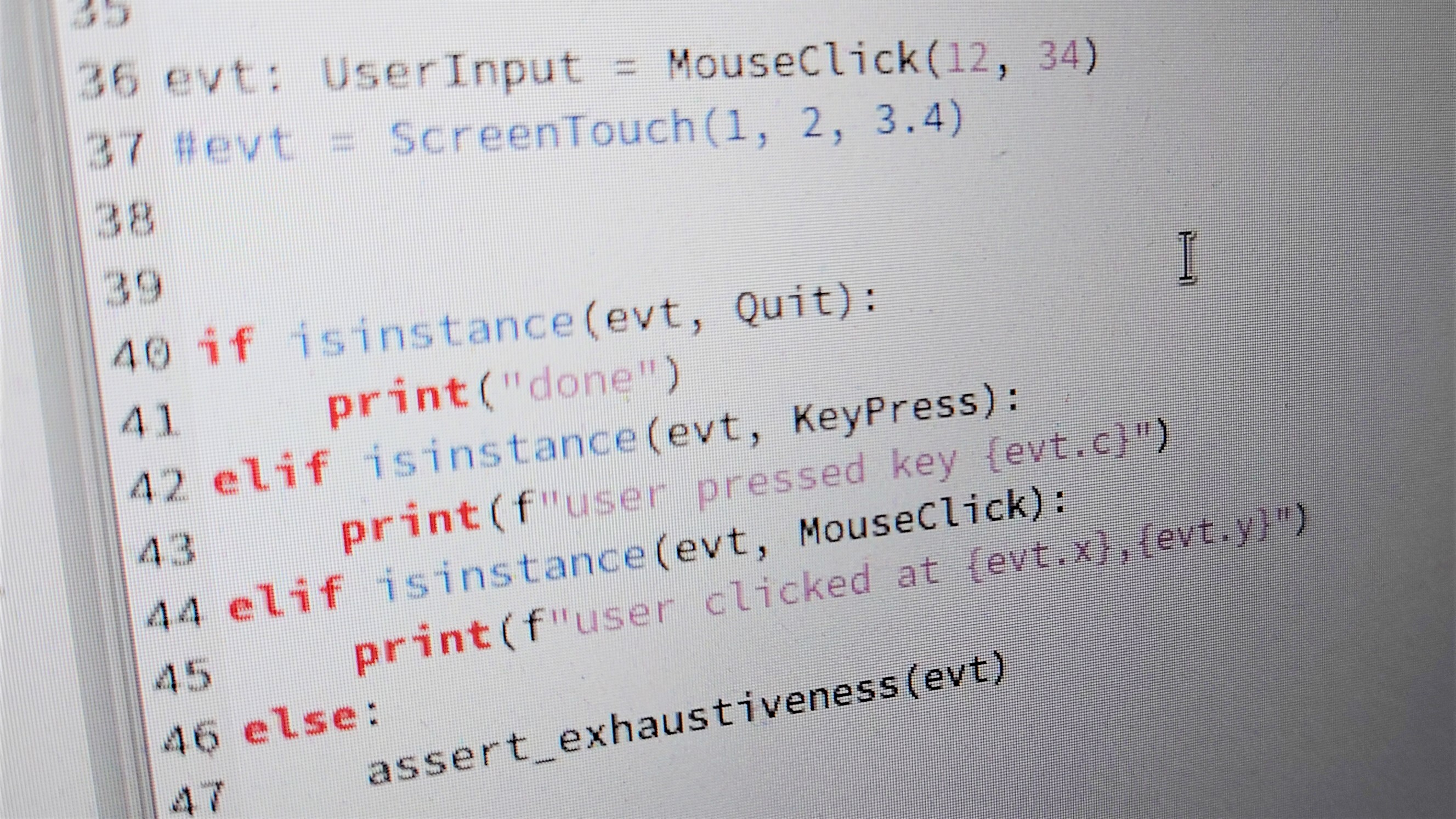

2. Static Typing

In the previous section we saw how the str part of Dict[str, Any] may cause problems, now let’s have a look at the Any part. I don’t want to enter into the general discussion of statically vs dynamically typed programming languages in all its facets here, but as far as program correctness is concerned there exists some evidence that static type checking reduces the effort and leads to better results when fixing bugs. In Python, such checks can be performed by mypy for code that is using type annotations. I want to encourage you to use these annotations all over your code, not only when working with configuration.

Looking at one example from above, start_server(port=os.environ.get("PORT", 80)), for a function that expects an integral value port this code fails if the environment variable PORT is set, because the entries of os.environ are always strings. You may know this by heart or not, but if the start_server() function is declared like start_server(port: int) then a check with mypy shows you that something is wrong:

server.py:6: error: Argument 1 to "start_server" has incompatible type "Union[str, int]"; expected "int"

Besides these basic checks, static typing provides an elegant way to limit the set of possible inputs accepted by your code. For example, when you have a configuration entry referencing a file, use a pathlib.Path rather than str and avoid having to deal with strings that are not valid file names. If there is a fixed number of possible values, use an enum.Enum to represent it. If only either one or another value may be specified, use a Union. If a value is optional, make it explicit through the use of Optional. By using the type system to formally specify what a value is allowed to be or not, you can use tools to discover code paths that you didn’t cover – or ones that can actually never happen.

One additional thing to consider, in particular when dealing with physical dimensions like duration, weight, distance, speed etc., is to abstract away the concrete unit and work with the dimension instead. For example, rather than declaring a configuration entry like, say, check_interval_s: float or check_interval_ms: int, declare it like check_interval: datetime.timedelta. You can then write most of your code in terms of these dimensions, calculate with them on an abstract level, and only convert them into a concrete value when working with external libraries, for example when calling time.sleep(check_interval.total_seconds()).

A final word of caution: in Python, type annotations have no validating effect at runtime. Even if all your code is annotated and passes type checking, if a variable a: int is a string at runtime then unexpected things will happen. Making sure that the actual data looks as you expected is the topic of the next section.

3. Early Validation

For most configuration values, there is a certain shape, type, or range of data that makes sense. Using static typing as described in the previous section is already an example of declaring a shape that a value must have to be usable. There may be other constraints, like minimum and maximum value, matching a certain regular expression, or pointing to another (existing) section of the configuration.

A simple way to perform validation is at the location where the configuration is used. For example, you could write

assert len(config.user.email) > 0 if config.port < 1024: raise ConfigError("please specify an unprivileged port")

or similar whenever you use these values.

However, this leads to a couple of problems:

- The value must be validated at every location where it is used, leading to code duplication. Alternatively, you need to remember whether it was already validated or not when you use it.

- If something is wrong, then the problem shows up only when the configuration value is accessed for the first time. This makes it harder to spot errors and takes more effort to check that a new configuration value is actually valid.

- As written above, in Python even if it says

port: intin the class declaration,config.portcould be a string at runtime. That is something that you definitely do not want to check every time you use the value.

Therefore I would advise to validate the configuration as soon as possible after program startup, and exit immediately if it is found to be invalid. Note that if you chose to represent configuration entries using appropriate types as suggested in the previous section, just parsing the configuration successfully already leaves you with a valid configuration in many cases (cf. Parse, don’t validate).

In terms of operations, validating early ensures that the program does not exit at some time long after starting because of invalid configuration. In terms of development, it makes life easier because you can just assume everywhere that the configuration data structure only contains valid values and can be used safely, like any other object in your program.

4. Declare Configuration Where it is Used

This last principle states that configuration entries should be declared close to the place where they are used, for example as a class in the same module as the code that uses it.

This rule can not directly be derived from the foundations described above, in that it does not necessarily contribute to using tools more efficiently, or to preventing or reporting bugs early. However, it has a couple of advantages in terms of software engineering, when compared with declaring all the configuration entries in a single place:

- The physical closeness helps navigating, for example it is easier to find the places where a certain configuration entry is used. Furthermore, if you are using a data structure that also defines the valid bounds for a configuration value, it makes sense to do that close to the code that is relying on these bounds.

- It helps to avoid using the same configuration entry in different, unrelated components. Assume you have an entry, for example something like

timeout, defined in a central place and accessible from all modules, then it is tempting to reuse that same timeout entry in various unrelated places rather than adding a new entry, naming and documenting it appropriately. If a configuration is defined locally in the module it is easier to see that this is a bad thing to do, for example you would most likely not importweb.http.config.client.timeoutin thedb.backendmodule to use it as a setting for your database connection pool. - When testing a component that takes configuration as a parameter, you only need to mock a configuration object with the locally used entries, rather than the complete configuration for the whole application.

The sub-configurations from each module can be assembled into a bigger class using composition or inheritance. In general I recommend composition, as inheriting from multiple small configuration classes is likely to cause naming conflicts at some point.

Putting the Pieces Together

So let’s have a look at how we can put the principles together into a small code sample. This example is heavily inspired by the approach described in Section 3.5 of the Scala Best Practices collection by Alexandru Nedelcu.

We have three modules, each locally defining their well-typed configuration classes. (For the sake of brevity I omit the import statements.)

### app/db/config.py class Backend(Enum): MYSQL = 1 POSTGRES = 2 SQLITE = 3 @dataclass class Configuration: backend: Backend pool_size: int ### app/server/config.py @dataclass class Configuration: port: int log_file: pathlib.Path ### app/user/config.py @dataclass class Configuration: name: str birthday: datetime.date

A class in, say, the app.user module, can take an instance of its local Configuration class in the constructor and work with it without having to worry about type mismatches or missing values. A unit test in the user module does not have to mock the whole app configuration.

Note that dataclasses are particularly well suited for this application because they cannot have declared but uninitialized members, contrary to normal Python classes. If a member is added to the dataclass declaration, then mypy reports all places where an instance is constructed without providing a value for the new member.

The main application living in a different module can then define an application-wide configuration class like this:

@dataclass class Configuration: version: Version user: app.user.Configuration server: app.server.Configuration db: app.db.Configuration

So far I have not discussed how you can actually create an instance and perform validation of this global configuration class. For simple cases like this the dacite library that converts dictionaries into dataclasses is very useful. Consider the following code:

# the JSON below could come from some configuration file raw_cfg = json.loads( """ { "version": "1.2.3", "user": {"name": "John Doe", "birthday": "1980-01-01"}, "server": {"port": 1234, "log_file": "access.log"}, "db": {"backend": "POSTGRES", "pool_size": 17} } """ ) # define converters/validators for the various data types we use converters = { Version: Version, datetime.date: datetime.date.fromisoformat, pathlib.Path: pathlib.Path, app.db.Backend: lambda x: app.db.Backend[x], } # create and validate the Configuration object config = dacite.from_dict( data_class=Configuration, data=raw_cfg, config=dacite.Config(type_hooks=converters), )

If this code is executed without an exception then we have a valid Configuration object like

Configuration( version=Version('1.2.3'), user=Configuration(name='John Doe', birthday=datetime.date(1980, 1, 1)), server=Configuration(port=1234, log_file=PosixPath('access.log')), db=Configuration(backend=<Backend.POSTGRES: 2>, pool_size=17) )

and I hope I could convince you that this is in every way a better method to pass configuration data around than just a dictionary with the parsed JSON contents.

Discuss this post on Hacker News: https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=22964910

![[PFN Day] BoF session: How to Improve Sharing of Software Components and Best Practices](https://tech.preferred.jp/wp-content/themes/preferred-research/assets/img/noimage.png)